The Garden at Charleston

The garden at Charleston today. Photographs © Penelope Fewster

While photographing the box of loose works on paper from Duncan Grant’s studio discussed in a previous post, we came across two items of particular interest. One is a small painting on lined notepaper posthumously attributed to Vanessa Bell, of a man tending to a flowerbed with a wheelbarrow at his feet. The other is a profile portrait sketch, likely to have been made by Grant. Although this sheet had been reserved and boxed up with other items in the Gift due to the drawing, it is the reverse of the work that is especially interesting in this instance; it is an envelope addressed to Duncan Grant, postmarked 1962, from Carters Tested Seed Ltd. These two items provide a wonderful insight into one of Bell and Grant’s shared passions and sources of artistic inspiration at Charleston: the garden.

Top: Vanessa Bell, , paint on lined paper, date unknown. CHA/P/1075/Recto. Bottom: Duncan Grant, CHA/P/1156/Verso. Photographs © The Charleston Trust

‘I wish you’d leave Wissett and take Charleston…It has a charming garden, with a pond, and fruit trees, and vegetables, all now rather run wild, but you could make it lovely.’

Letter from Virginia Woolf to Vanessa Bell, May 1916.

Grant and Bell were enthusiastic gardeners who worked tirelessly to transform the muddy, overgrown gardens first encountered by Woolf in 1916 to the dense riot of colours, scents and textures it was later to become. First used to supply the household with fruit and vegetables during the First World War, towards the end of the conflict Bell turned her attention towards improving the garden as a space for pleasure. Roger Fry assumed the role of garden designer, drawing up his first plans for the walled garden as early as 1917. Employing the rational aesthetic principles he championed in his writing, Fry created a grid of intersecting paths and box hedges which framed a lawn inlaid with a small rectangular pool. Within this framework richly scented, brightly coloured and dramatically shaped flowers were planted, interspersed with subtle silver foliage; red-hot pokers, hollyhocks, foxgloves, globe artichokes, roses, poppies, lavender, alliums, nasturtiums, dahlias and zinnias.

Grant in particular was an obsessive plant collector, and regularly purchased seeds to be cultivated at Charleston – the envelope from Carters Tested Seeds Ltd. is likely to have once contained a catalogue or invoice for new acquisitions. In addition to employed gardeners, Bell and Grant were helped in the garden by Maynard Keynes, who could often be found on his hands and knees weeding the gravel borders.

Duncan Grant, Walled Garden at Charleston, circa 1965, oil on canvas, 49.5 cm x 60 cm. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

It is unsurprising that the air of creativity fostered inside the house, with its painted surfaces and modern artworks, was to spill out into the garden. The spaces surrounding the house assumed numerous roles: an outdoor studio with an unlimited supply of props for painting; an al fresco gallery ideal for displaying sculptures and art-school models collected by Grant; secluded spots offering quiet and privacy for contemplation, reading and writing; a perfect auditorium for performing theatricals complete with hand-made props and elaborate costumes.

Photograph of Julian, Quentin and Angelica Bell with Janie Bussy, performing a play about Damon and Phyllis in the walled garden, 1935. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

Photograph of Julian, Quentin and Angelica Bell with Janie Bussy, performing a play about Damon and Phyllis in the walled garden, 1935. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

The house seems full of young people in very high spirits, laughing a great deal at their own jokes… lying about in the garden which is simply a dithering blaze of flowers and butterflies and apples.

Vanessa Bell, 1936.

Bell fondly discussed the garden at Charleston in letters to friends and family, and would regularly paint outside, even in the depths of winter. When the weather was bad, she brought the garden inside by collecting flowers, fruit and seed heads to feature in still life compositions. Bell’s granddaughter, Virginia Nicholson, refers to her passion for the garden in a discussion of the murals in nearby Berwick Church, painted by Bell and Grant in the 1940s:

‘Vanessa’s Virgin Mary is Angelica, and true to Renaissance iconography she kneels before the Angel Gabriel in a garden – but this one is walled with flint, pathed with gravel and edged with grey-green lavender. Her Madonna lilies were probably culled from Vanessa’s own borders. The garden is Charleston and Vanessa’s painting is a celebration of her private heaven.’[1]

Vanessa Bell, The Annunciation, mural, c. 1942. Berwick Church, Sussex.

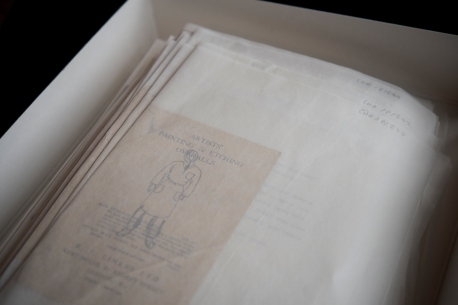

When the Charleston Trust was formed and the house restored in the 1980s, celebrated landscape architect Sir Peter Shepeard reconstructed the garden to Fry’s own plans, searching for references in paintings, early photographs and archived letters in order to create a faithful reproduction. While the walled garden was largely neglected in Grant’s old age, many of the original shrubs did survive and were retained. The new plan drawn up by Shepeard’s is still used by Charleston’s Head Gardener, Mark Divall, who works hard throughout the year to maintain the beautiful and unusual gardens which enchant so many visitors today. Annotated, dog-eared and stained from over twenty years of use, this document has acquired its own relic-like status and sits comfortably alongside the two Gift items. Together they hint at a visual biography of a space that was of vital importance to the creative and progressive way of life at Charleston.

The walled garden restoration plans, 1985. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

–

Read more about Mark Divall and his work at Charleston in his interview with The Garden Edit

[1] Quentin Bell & Virginia Nicholson, Charleston: a Bloomsbury House and Garden (Frances Lincoln, London, 1997). p. 147