Buildings – contrary to popular thought – are not inanimate objects. They live and breathe, and like humans, have an outside and an inside, a body and a soul.

Daniel Libeskind, Breaking Ground: Adventures in Life and Architecture. [1]

Saw my old room – so strange with the ink splashes and shelves as of old. I could write the history of every mark and scratch in that room, where I lived so long.

Virginia Woolf, Journal, 30 January 1905. [2]

Spaces and buildings inhabit our world and imaginations. Old mills, ruined castles, enchanted forests, damp cellars, derelict cottages, cobwebbed attics, domestic wardrobes and chests of drawers, each have their own unique poetic sensibility. These spaces are theatres that shape our thoughts, memories and desires. In short, the enclosures and fabrics of the houses and buildings we grow up in, live within, visit and dream about at night are building blocks for the imagination.[3]

The idea of a reflexive correspondence between house and inhabitant is one that members of the Bloomsbury Group relate to in their memorial writings about the houses of their pasts. In 1922 Lytton Strachey wrote:

‘Those curious contraptions of stones and bricks . . . in which our lives are entangled as completely as our souls in our bodies – what powers do they not wield over us, what subtle and pervasive effects upon the whole substance of our existence may not be theirs.’ [4]

This statement has clear relevance to Charleston today. The corridors, rooms, hallways and stairwells their are imbued with the spirits of the past inhabitants. No visitor can fail to notice the emotionally textured interiors, the suggestive qualities of light and darkness and the evocative power of atmosphere the house inspires. The visitor to the house experiences it viscerally; to physically walk through the spaces that Grant and Bell did is not to merely think about those artists but to be in the ‘physical presence of their actualised past’, to be immersed in the fabric of their surviving home.’ [5]

Painting, Duncan Grant, ‘Charleston barns’, circa 1959, oil on canvas, framed, signed, 54.7 cm x 63.4.

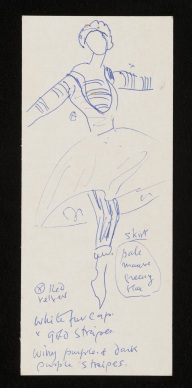

Sketches of buildings and interiors haunt what has been revealed in the Angelica Garnett Gift thus far. Below are some examples of these pieces that have come to light in the attic.

Piece from the Angelica Garnett Gift. Not catalogued at present.

Piece from the Angelica Garnett Gift. Not yet catalogued.

The Bloomsbury Group lived in a period of changing thought in regards to buildings, architecture and space. Having inherited a fossilised Victorian culture and stiff Victorian houses with their clear cut boundaries between private and public spaces, the group represented something radically new; rooms and houses lost their material feel and functions and became metaphors of a less solid reality. These were now spaces imbued with the spirit of their inhabitants and visitors, interiors that now expressed intellectual and spiritual energy, an exquisite refinement and an innovative zest. [6] Pictures from the Gift underline this enduring fascination Grant and Bell had with interiors, rooms and buildings.

[1] Daniel Libeskind, Breaking Ground: Adventures in Life and Architecture, (London: John Murray, 2005), p.5.

[2] Virginia Woolf, A Passionate Apprentice: The Early Journals 1897-1909, ed. Mitchell . Leaska, preface Hermione Lee (London: Pimlico, 2004), p. 230.

[3] For more on the conceptual link between poetics and physical space, see: Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space: The Classic Look of How We Experience Intimate Places (Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 1994).

[4] Lytton Strachey, Lytton Strachey by Himself: A Self Portrait, ed. and intro. Michael Holroyd, (London: Abacus, 2005), p.21.

[5] Nuala Hancock, Charleston and Monk’s House: The Intimate House Museums of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012), p. 39.

[6] For more information on the Bloomsberry Group and changing perceptions of architecture, see: Victoria Rosner, Modernism and the Architecture of Private Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005).

CHA/PH/2. Photograph. Nijinsky in the Siamese Dance from ‘Les Orientales,’ 1911, by Druet. 26.5 x 43.6 cm. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

CHA/PH/2. Photograph. Nijinsky in the Siamese Dance from ‘Les Orientales,’ 1911, by Druet. 26.5 x 43.6 cm. Photograph © The Charleston Trust