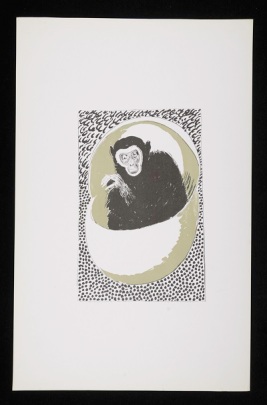

‘This egg changed into a stone monkey’ Duncan Grant, Chinese folk-lore and lithographs

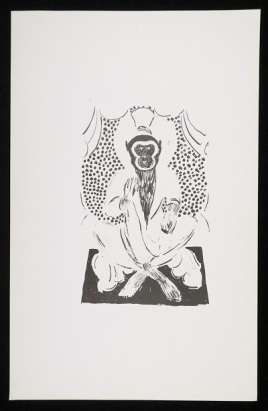

(top) CHA-P-1602, Duncan Grant, colour proof, This Egg Changed into a Stone Monkey, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (bottom) CHA-P-1619, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Monkey… I hereby promote you to be the Buddha Victorious in Strife, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

(top) CHA-P-1602, Duncan Grant, colour proof, This Egg Changed into a Stone Monkey, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (bottom) CHA-P-1619, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Monkey… I hereby promote you to be the Buddha Victorious in Strife, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

Now we have moved onto cataloguing larger works we are uncovering many intriguing and beautiful works but what especially caught our eye this week was a collection of original lithographs and colour proofs by Duncan Grant. Up in the Charleston Attic we are used to playing detective and after some research we learnt that this collection of forty pieces are a result of a commission in 1965 by The Folio Society to produce illustrations for its publication of Arthur Waley’s translation of Monkey: a folk-tale of China, more commonly known simply as Monkey. The translation is an abridged version of the 16th century Chinese novel Journey to the West by We Cheng of the Ming dynasty.

Monkey is widely considered to be one of the four great classical novels in Chinese literature and is based on the true story of a pilgrim named Hsuan Tsang. In the seventh century Hsuan Tsang travelled to India to procure the true Buddhist Holy Books to translate into Chinese, making a great contribution to the development of Buddhism in China. By the tenth century the pilgrimage of Hsuan Tsang had become the subject of fantasy and folk-lore and from the thirteenth century till the present day the story has been constantly presented and re-imagined on the Chinese stage.

The novel takes the tale of Hsuan Tsang and presents it as a combination of folk-lore, allegory, religion, history, anti-bureaucratic satire and pure poetry. At the outset of the novel Buddha seeks a pilgrim who will travel West to India with the hope of retrieving sacred scriptures by which the Chinese people may be enlightened. A young monk called Tripitaka volunteers to undertake the pilgrimage and on his journey he encounters the Monkey King and two monsters in human form named Sandy and Pigsy. The theme of the novel is mans journeying through the difficulties of life with Monkey representing the instability of genius, Pigsy symbolising physical appetite and brute strength while Sandy embodies sincerity. Hatched from a stone egg and given all the secrets of heaven and earth Monkey can transform himself into seventy-two image such as a tree, a beast of prey or an insect and can ride on clouds, travelling 108,000 miles in a single somersault.

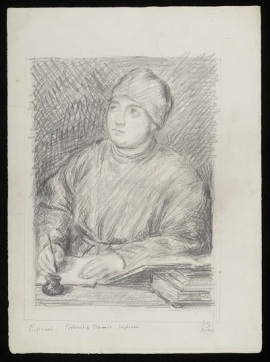

Grant produced twelve lithographs for the 1965 publication, with examples of eight of these works in various stages of completion being found in the Angelica Garnett Gift so far. Previously he had been commissioned to design the jacket for the 1942 edition of Monkey. In the cover design he wound the image of the Monkey King around the entire book and at the suggestion of the publisher David Unwin the title details of the book were put at the back, so as to be in keeping with the reverse nature of Chinese literature. The pieces found in the Gift show the various stages of colour proofing Grant would have completed before he was happy with the final image. We see the same image being produced repeatedly with different colours added or taken away. It appears that Grant worked to apply a deliberately Chinese style for some of these works. We know that there were established links between China and the Bloomsbury group. Julian Bell, Vanessa’s son, lived and worked in China, sending Chinese silks, porcelains and ceramics to his mother at Charleston and Roger Fry delivered Slade Lectures on Chinese Art at Cambridge. Some of these ceramics and other objects of Chinese origin remain on display at Charleston today, for example the cast of a sixth century AD Chinese Bihisattva Kuan-Yin, Goddess of Mercy which was given to Grant and Bell by Fry is in the artists former studio.

(top) CHA-P-1609, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Wild and fearful creatures, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (second down) CHA-P-1606, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Wild and fearful creatures, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (third down) CHA-P-1605, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Wild and fearful creatures, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (bottom) CHA-P-1760, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Dust-jacket for Monkey 1942, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

Grant’s and also Vanessa Bell’s enthusiasm for lithography was encouraged by French artist, and friend to the Bloomsbury artists, Pierre Clairin. Professor of Lithography at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Clairin was often Grant and Bell’s host in Paris and had much experience of the procedure of lithography. Examples of his small and delicate colour lithographs can be seen on the walls of Charleston to this day.

Having gained knowledge of lithography in Paris it was closer to home where Grant would find a patron, or patrons, to allow him to develop his interest in producing prints and lithograph illustrations. The Ladies of Miller’s, sisters Frances Byng-Stamper and Caroline Lucas, opened a gallery on the High Street in Lewes in 1941. With a passion for art, literature and music and the support of Maynard Keynes, the chairman for the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA), the sisters secured the pick of touring exhibitions and presented shows with sculpture by Rodin, Maillol and Epstein and paintings by Bonnard, Picasso and Derain. Clive Bell was heard to joke that ‘Lewes had become one of the cultural capitals of Europe’ as the sisters began publishing books, instigating lectures, concerts, began a shortly lived art school at which Grant and Bell were teachers and organised a retrospective of the Omega Workshops.

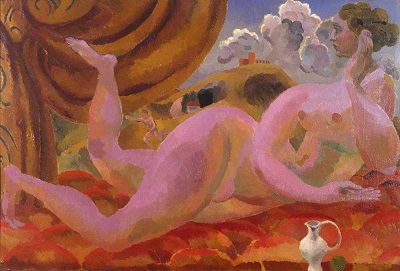

At the end of the war in 1945 the sisters were to receive an exhibition by CEMA of European lithography from 1792 to the present day. To this they added their first publication of a portfolio which contained two lithographs each by one of the Ladies of Miller’s herself, Caroline Lucas, Vanessa Bell, South-African born painter Ensin du Plessis and Duncan Grant. This first publication was an resounding success with the public responding avidly and the one hundred copies of Eight Lithographs which was priced at five pounds being sold within weeks. This positive public reaction led to the Ladies of Miller’s joining forces with the Redfern Gallery in London in 1948 to form the Society of London Painter-Printers. The gallery at that time was under the direction of Rex Nan Kivell and was considered to be the principal outlet for contemporary prints. That year, Six Lithographs by Grant and Bell was published. The lithographs they produced for this work had an undeniable charm, their anecdotal subject matter appealing to the masses with portraits of their grandchildren, still lives of flowers and fruit and images of domestic animals. The working relationship between Grant, Bell and the Ladies of Miller’s continued until the Press was disbanded in 1954. Although Grant accepted occasional invitations to produce lithographs and etchings following Bell’s death in 1961 the most productive years of their collaboration concluded with the dissolving of the Press.

(top) CHA-P-1603, Duncan Grant, colour proof, She threw down her ball, and it fell exactly on the middle of Ch’ens black gauze hat, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (second down) CHA-P-1594, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Bodhisattva, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (third down) CHA-P-1622, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Monkey forgot all about the Star Spirit and soon left him far behind, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (bottom) CHA-P-1608, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Death of the dragon, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

Much has been written about the art and private lives of the Bloomsbury artists yet little attention has of yet been paid to their graphic work. Although it forms only a fraction of their artistic oeuvre, Grant’s Monkey illustrations demonstrate clearly his ability to produce light-hearted, delicate and engaging lithographs. Grant, echoing Roger Fry’s desire to dismantle the barriers between high and applied art, would accept any printing commission that was offered to him, although of course payment for artwork would surely have also been a motivating factor to print. Arthur Waley’s translation of Monkey remains one of the most read English language versions of the novel and one can imagine that Grant’s illustrations have provided delight and entertainment to many throughout the years and hopefully will continue to in years to come.