Book illustrations and jacket designs by Duncan Grant

As Charleston looks forward to a weekend of Centenary celebrations, ‘The Attic’ is being specially prepared to open its doors for visitors this Sunday 16 October. Rarely on show to the public, the space, accessed by narrow, steep stairs at the top of the farmhouse was once Vanessa Bells’ studio and now stores Charleston’s extensive archive collection and works of art.

My first blog post as Charleston’s ‘Attic intern’ showcases some of Duncan Grant’s book illustrations and book jacket designs from the 1960s. Newly catalogued from the Angelica Garnett Gift is a collection of Duncan Grant’s correspondence regarding his illustrations for a previously undiscovered short story by Virginia Woolf featuring ‘Nurse Lugton’ and a book jacket design for a novel by Margaret Lane called A smell of burning.

Nurse Lugton’s Curtain.

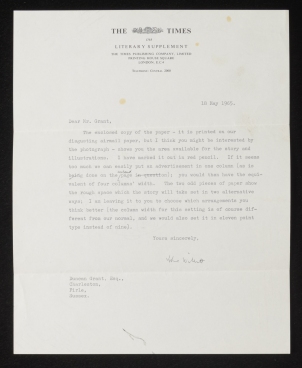

A letter dated 18 May 1865 written to Duncan Grant by John Willett of The Times Literary Supplement [TLS] discussed available space in the supplement for the ‘story and illustrations’:

CHA/E/253, ‘Letter to Duncan Grant from John Willett deputy editor of The Times Literary Supplement’, 18 May 1965. © The Estate of Duncan Grant. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

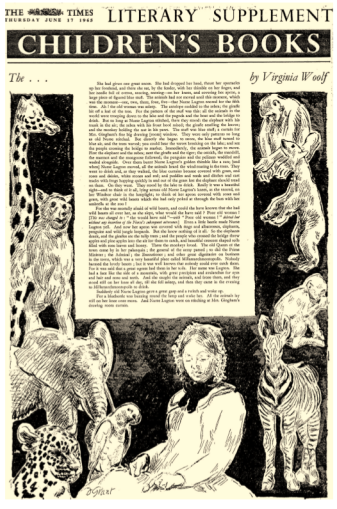

Further research has revealed that ‘the story’ referred to in the letter was a children’s tale written by Virginia Woolf featuring a character named ‘Nurse Lugton’. It had been newly discovered in 1965 by children’s fiction author, Wallace Hildick (1925-2001). According to an article written by Hildick published in TLS of the 17 June 1965, this story had been found in the second volume of the Mrs Dalloway manuscript acquired by the British Museum in 1963. Hildick edited the story and it was framed with illustrations drawn by Duncan Grant and published alongside the newspaper article. [1]

‘Children’s Books, The ….. by Virginia Woolf’, The Times Literary Supplement, Thursday, June 17, 1965; pg. 496; Issue 3303. © News International Associated Services Limited Gale Document Number: EX1200337421.

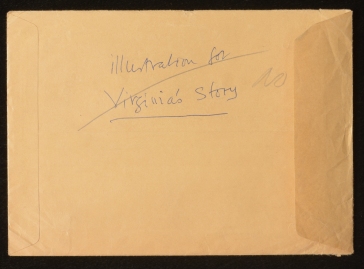

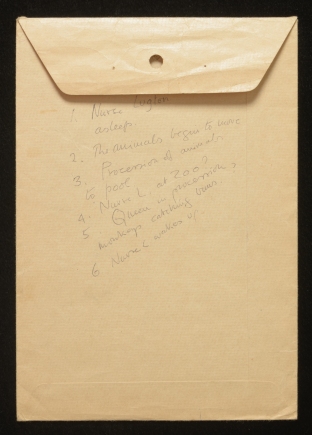

Also in the archives from the Angelica Garnett Gift are two manila envelopes which refer to Virginia Woolf’s story; item CHA/E/252 once contained an illustration and item CHA/E/251 is inscribed by Duncan Grant with a handwritten list of illustrations, such as ‘1. Nurse Lugton asleep’ which probably refers to the illustration of Nurse Lugton in the Times article.

CHA/E/252, verso, manila envelope, © The Estate of Duncan Grant: Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

CHA/E/251, verso, manila envelope with inscription, © The Estate of Duncan Grant: Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

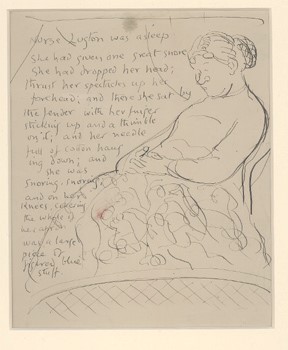

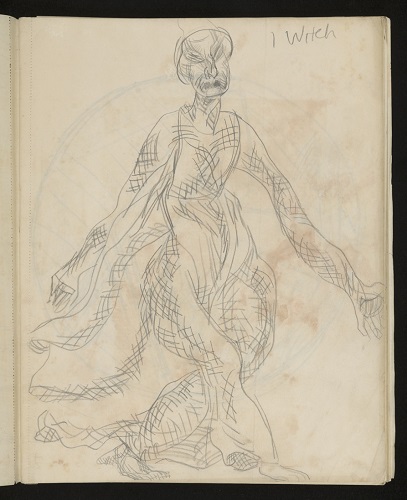

The Virginia Woolf Collection at the E.J. Pratt Library at the Victoria University in the University of Toronto holds a Duncan Grant drawing entitled Nurse Lugton was asleep with handwritten notes by Duncan Grant of the opening passage of the story, first published in 1965 in a collection as Nurse Lugton’s Curtain. In this version of the drawing Nurse Lugton looks somewhat different to her Times Literary Supplement counterpart.

Duncan Grant (1885-1978), Nurse Lugton was asleep, study for a page of Nurse Lugton’s Curtain by Virginia Woolf PR6045.O72 N8 1991 VUWO. Photograph: Victoria University in the University of Toronto.

A smell of burning

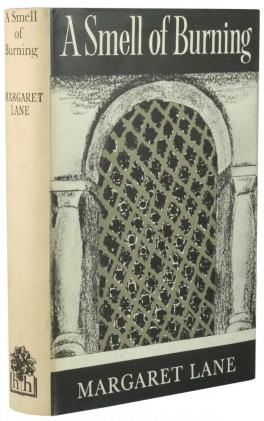

A letter from Roger Machell of Hamish Hamilton to Duncan Grant dated 10 August 1965 refers to Grants interest in designing a jacket for a novel by Margaret Lane (1907-1994) called A smell of burning.

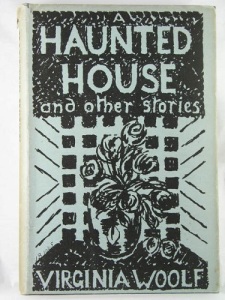

Margaret Lane, A smell of burning, 1965, Hardcover, 1st Edition. Published 1965 by Hamish Hamilton. Image: Goodreads.com. Cover design by Duncan Grant.

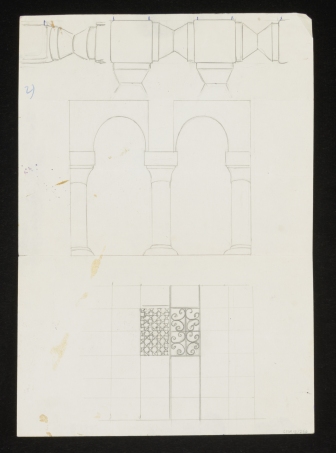

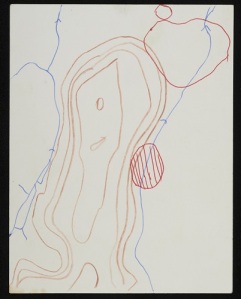

The letter contains two sketches, one by Margaret Lane’s husband, Lord Huntingdon and the other by Margaret Lane herself ‘showing the kind of window that might make a suitable basis for a design’.[2]

CHA/P/ 3122, Lord Huntingdon, Drawing (1), ideas for jacket design for A smell of burning, 1965. © The Estate of Duncan Grant. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

CHA/P/ 3121, Margaret Lane, Drawing (2), ideas for jacket design for A smell of burning, 1965. © The Estate of Duncan Grant. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

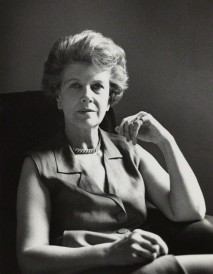

Author and critic Margaret Lane was the former wife of Brian Wallace, son of writer, Edgar Wallace. She was the second wife of Lord Huntington whom she married in 1944. The couple lived at Black Bridge House in Beaulieu where her artistic talents were expressed ‘Bloomsbury’ style: according to Elizabeth Jenkins writing Margaret’s obituary for the Independent, her ‘creative faculty found expression in decorating surfaces [….] and in her later life the hobby of covering screens, pasted with a collage of scraps, wonderfully collected, each of them a work of art’.[3]

Godfrey Argent, Margaret Lane (Lady Huntingdon), bromide print, 28 July 1969, Photographs Collection National Portrait Gallery x165942. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

[1] Wallace Hildick, ‘Virginia Woolf for Children?’, The Times Literary Supplement (London, England), Thursday, June 17, 1965; pg. 496; Issue 3303.

[2] CHA/E/255, ‘designing a jacket for A smell of burning’, Letter from Roger Machell (editorial director) of Hamish Hamilton (publishers) to Duncan Grant, 10 August 1965, The Charleston Trust Archives.

[3] Elizabeth Jenkins, ‘Obituary Margaret Lane’, Independent, Thursday 17 February 1994, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-margaret-lane-1394635.html

![13495117_1521270931304962_3460946581219286778_n[1].jpg](https://thecharlestonattic.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/13495117_1521270931304962_3460946581219286778_n1.jpg?w=450)

![GraceHiggenscTonyTree[1].jpg](https://thecharlestonattic.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/gracehiggensctonytree11.jpg?w=500)

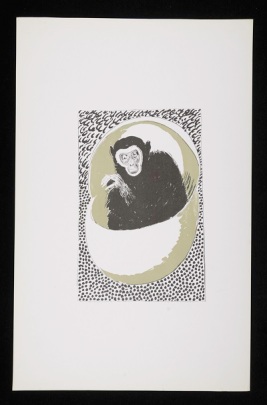

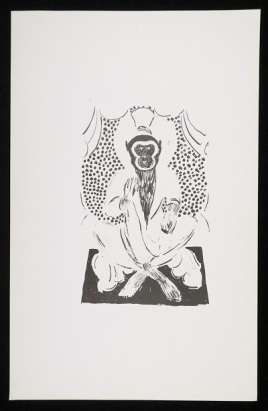

(top) CHA-P-1602, Duncan Grant, colour proof, This Egg Changed into a Stone Monkey, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (bottom) CHA-P-1619, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Monkey… I hereby promote you to be the Buddha Victorious in Strife, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

(top) CHA-P-1602, Duncan Grant, colour proof, This Egg Changed into a Stone Monkey, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (bottom) CHA-P-1619, Duncan Grant, colour proof, Monkey… I hereby promote you to be the Buddha Victorious in Strife, ink on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust