In 1910, at the age of twenty-five, Duncan Grant’s career began to take off. His work was beginning to be recognized, having been shown more widely, and the period of 1908-11 is viewed as being one of rapid productivity for Grant as an artist. ‘He was always very productive,’ Douglas Blair Turnbaugh wrote, ‘[Though] at this time…in his early twenties, his creative genius was beginning to be recognized, and he was considered a leading contributor to the Post-Impressionist movement in England…he had [already] a thorough understanding of French and Italian schools of the past, and highly developed technical skills.’

Duncan Grant, from various photographs taken by the artist in preparation for his studies, George Leigh Mallory, 1912, 46 Gordon Sqaure, Photographs © Estate of Duncan Grant

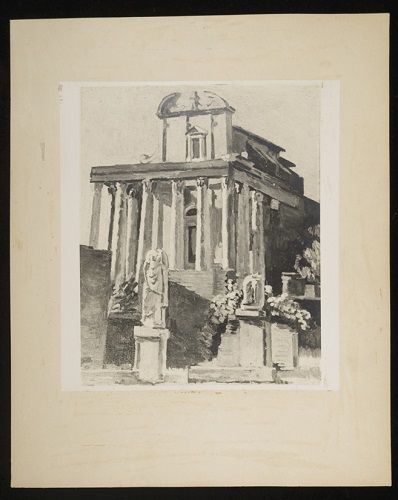

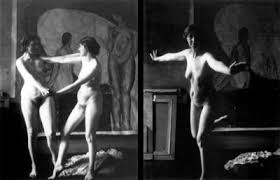

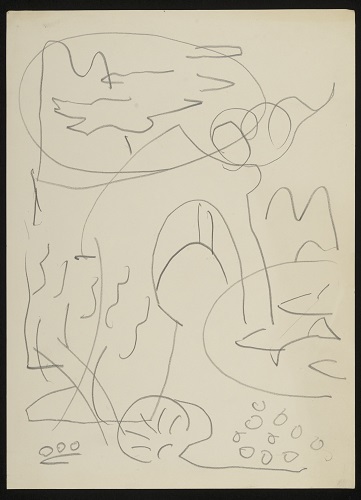

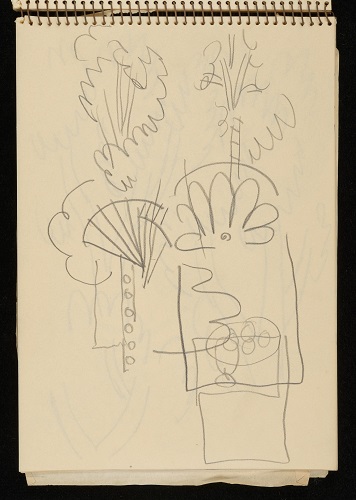

Richard Shone cites ‘[Grant’s] early portraits of his friends and… relations [as] encapsulate[ing] the sound technical accomplishment [that]he had achieved by his early twenties.’ In 1908, after returning from Paris where he had studied classical painting in the Louvre, Grant was residing at 21 Fitzroy Square in London. It was here that he seriously began painting portraits. As Blair Turnbaugh observed; ‘He took a studio near Belsize Park Gardens and began a series of brilliant portraits of everybody within his reach, including…new friends, and many relatives ….’ In his studio on the first floor, Grant invited friends and family to pose for his painting and drawings to save the expense of hiring professional models. He liked to photograph his models, and ‘These photographs were references for some of Duncan’s erotic drawings and paintings’, as erotic photography was back then illegal and utmost discretion was essential.

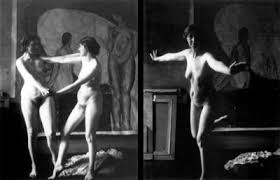

Duncan Grant, preparatory photographs, Vanessa Bell and Molly MacCarthy, 1913, taken in the artists’ studio at 46 Gordon Square, Photographs © Estate of Duncan Grant

Grant also posed naked himself for photographs to be taken in his studio. Between 1909 and 1911, he produced of succession ‘youthful’ self-portraits that, in characteristic face-on, close-up style, were ‘intimate and direct’, as identified by Shone. In choosing to portray himself unabashedly, his apparent ease could be seen as a reflection of the intense pleasure he was experiencing in his personal life.

Duncan Grant, Study For Composition (Self-Portrait In Turban) (1910), oil paint on canvas. Photograph © National Gallery

Grant and John Maynard Keynes were lovers during the early years of Grant’s initial critical acclaim, and they remained so until about 1910. Happily, this relatively brief romantic period of theirs did not deter their friendship, which prevailed until Keynes’ death. Grant’s biographer Frances Spalding thought it telling of Grant and Keynes’ relationship that, ‘…when he reminisced about th[eir] affair, Duncan gave his close friend Paul Roche the impression that Keynes ‘was closer than anyone except perhaps Vanessa [Bell], and even closer than her in some respects…in the uncluttered recognition one male can have for another.’

Duncan Grant, Portrait of John Maynard Keynes (1917-18), oil paint on canvas. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

Indeed; ‘The significance of Maynard for Duncan went very deep and in old age…Before the end of [that] June [of 1914] he had fallen in love with Maynard and experienced an immediacy of rapport greater than he had ever known.’ This relationship would no doubt have heightened Grant’s sense of creativity s as he became more confident with his sexuality. As Spalding put it, ‘Maynard…liberated Duncan through his own attraction to the genuine and that which was without pretence.’ It helped greatly that Keynes himself had been in a liberal environment when he was a student, ‘[at] Kings College Cambridge [where] homosexuality ha[d] become…rampant.’ in the early 1900s.

Years later, when Roche sat as a model for Grant, Roche observed how he worked, and saw that in his style, Grant had what he saw as a ‘determination not to please [aesthetically] except by telling the truth, and telling the truth through the intransigent beauty of paint,’ Perhaps an element of the openness that Keynes had shared with Grant had found itself within Grant’s portraiture style as he captured his chosen sitters.

Duncan Grant, Paul Roche with leg raised; date unknown, charcoal and gouache. Photograph © Christies 2015

In the summer of 1910, Grant and Keynes holidayed together in Greece and Turkey, and took delight in photographing each other naked against the backdrop of the aged classical landscape. Christopher Reed saw the activity of picture-taking as Keynes’ and Grants’ way of ‘enacting the links they perceived between ancient and modern homoeroticism.’, and this was therefore a kind of an affirmation of sexuality; ‘…free of the repressive structures of [their] own culture[s].’

For Grant, it would have brought into clearer focus through the lens in his mind, the image of the classical male nude; ‘out of doors,.’ Bathing (1911) captures Grant’s idealised version of the male nude, aptly classicized in following of his preferred artistic style. The work was praised; namely, The Spectator remarked that, ‘…the figure scrambling into the boat in the background is a noble piece of draughtsmanship…[the work] gives an extraordinary impression of the joys of lean athletic life.’ Grant hired a model which he photographed in his studio in preparation for the work, allowing him the freedom as well as the accuracy to produce the life-size panorama that came to be so successful.

Duncan Grant, Bathing (1911), oil paint on canvas, Photograph © Tate.

Duncan Grant’s relationships with his models have been much looked at and written about, as they are interesting and complex; they were an integral part of his work and life. Though he made studies of men and women alike; ‘Integral to his creative process…attractive men were as vital a source for Duncan ‘s creative imagination as women were for Picasso’s.”, and he drew his lovers.

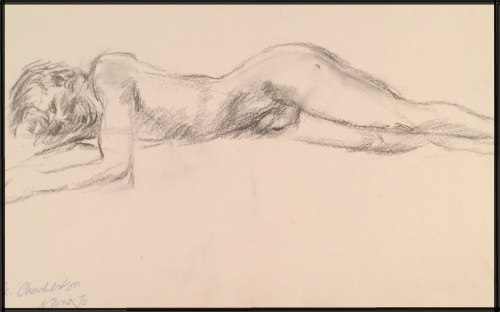

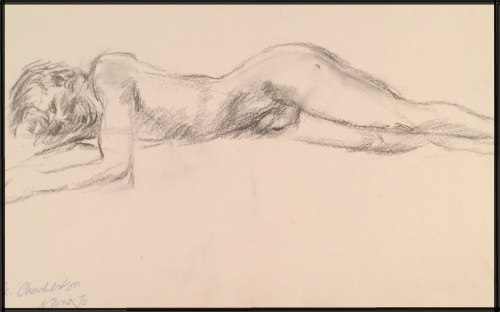

CHA/P/2630 Duncan Grant, study of female nude, charcoal on paper, Photograph © The Charleston Trust

CHA/P/2629 Duncan Grant, study of female nude, charcoal on paper, Photograph © The Charleston Trust

The sitters depicted in these sketches of his that we have unearthed this week as part of the Angelica Garnett Gift are less familiar to us. Grant used numerous models in his work throughout his lifetime; some who were paid, though many were family, friends, close or acquaintances.

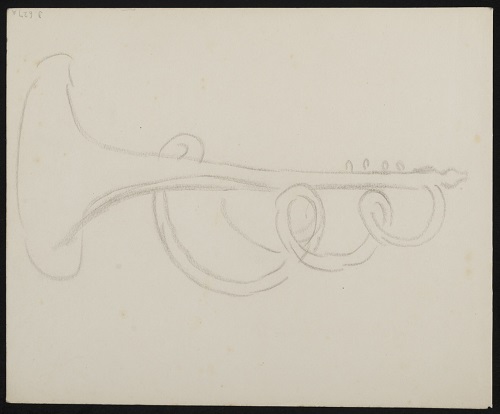

The two sketches of the female nudes are drawn with their heads turned away from us; their bodies twisted slightly away from the way they are facing, a pose subtly characteristic of Grant’s nudes. These two females were paid models who sat for Grant in about 1930. As a more established artist, Grant would have been able to afford to do this more than he had done so in his early career. The two sketches of the male nudes, both signed and dated, are of friends of their artist. Their inscriptions; ‘Mark, Charleston, 4th June ‘70’, and, ‘EC Farah, ‘65’, refer to the model, date and the place they were done. (Charleston, in the case of the 1970 drawing), as stylistically, we can attribute the works to Grant although he did not sign them.

CHA/P/2629 Duncan Grant, study of male nude, charcoal on paper, (1970), Photograph © The Charleston Trust

CHA/P/2634 Duncan Grant, study of male nude, charcoal on paper, (1965), Photograph © The Charleston Trust

From the relaxed way they hold themselves, as well as the intimate perspectives from which they are drawn, there is the sense that all of the sitters felt comfortable exposing themselves to Grant for the sake of his art, as was often the case. The sense of truth expressed in the body laid bare is heightened when it is expressed by creative means, and Duncan Grant made no secret in asserting his creativity.

![0 T UMAX PowerLook III V1.5 [2]](https://thecharlestonattic.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/cha-p-174avb.jpg?w=500&h=395)