New Faces at Charleston visit Tate Britain’s Queer British Art

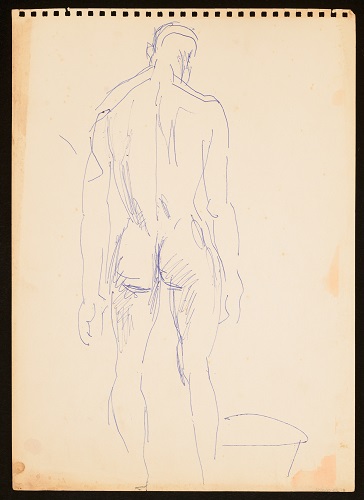

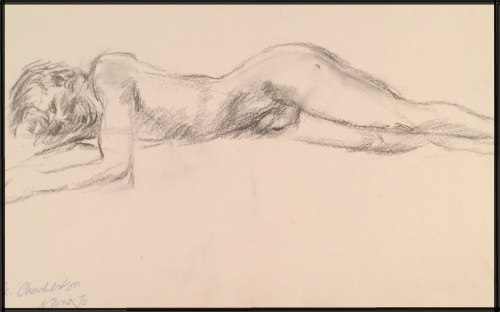

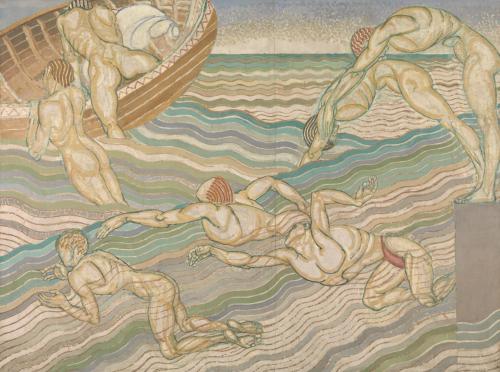

Duncan Grant, Bathing, 1911. Oil paint on canvas. Photograph © Tate.

Duncan Grant, Bathing, 1911. Oil paint on canvas. Photograph © Tate.

We have just joined Charleston as interns to finish cataloguing the Angelica Garnett Gift of paintings and drawings by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant.

By way of introduction, we visited Tate Britain’s exhibition Queer British Art: 1861-1967 which runs until 1 October. The exhibition ‘explores connections between art and a wide range of sexualities and gender identities’ during the century before the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967.[1]

Diana says ‘On entering the exhibition the initial impression is of a conventional Victorian display of classical sculpture and paintings in a somewhat gloomy setting. Then as my eyes adjusted I could see that the curators have selected the artworks with an eye to a queer aesthetic. The muscular male nude ‘The Sluggard’ (1885) by the highly successful Lord Leighton, contrasts with the delicate drawings of Simeon Solomon, whose life ended in poverty after a criminal prosecution. For me, the exhibits raised the question of what could and could not be shown in public. By-and-large, the focus is on what was displayed during the artists’ lifetimes.’

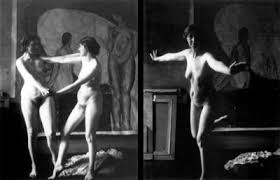

‘Leaving the dark Victorian galleries, it came as something of a relief to enter a much lighter room focusing on ‘Bloomsbury and Beyond’. Duncan Grant’s ‘Bathing’ (1911) dominates this room and is accompanied by Grant’s private drawings from the Angelica Garnett Gift which were lent by Charleston. Grant’s work is complemented by portraits of people linked to the Bloomsbury Group, such as Paul Roche, which look out boldly into the room. In these pictures, straightforward contemporary settings replace the classical allusions which had made earlier works acceptable to the public.

‘The scope for different identities is examined in the next room on ‘Defying Convention’. A highlight here is Laura Knight’s wryly-titled ‘Self Portrait’ (1913) where the artist shows herself fully clothed and painting a female nude, prompting the audience to consider whose sexuality is on display.’

Vanessa adds ‘Something that struck me in the exhibition was the attention given to clothing, the dressed and undressed body, and the influence this had in signifying or subverting ideas of queerness. Symbolising the importance of clothing in the exhibition was Roger Fry’s portrait ‘Edward Carpenter’ (1894). Painted with a proud stance Carpenter’s long dark coat is referred to as a ‘very anarchist overcoat’. His coat is no longer merely a thing to keep him dry, it is a thing that represents his socialist ideas, reflecting his activism for the rights of homosexuality.’

‘A personal highlight from the exhibition was William Strang’s ‘Lady with a Red Hat’ (1918). In this portrait Vita Sackville-West wears an incredible red hat and is posed rather elegantly. We learn of her dismissal of modern conventions as she often wears men’s clothing and has a male persona named ‘Julian’. This portrait acts as a binary into Sackville-West’s life. On the one hand she is shown as a fashionable woman of the time, on the other we see how she hides her male persona behind the very clothes she wears, subverting the perception of the viewer away from the ‘Julian’ and hinting at her complex sexuality.

‘Charles Buchel’s portrait of lesbian writer ‘Radclyffe Hall’ (1918) further suggests how dress can reflect identity. Encapsulating women’s fashionable clothing of this period, Hall wears a skirt and jacket. Predominantly worn by men, the addition of a cravat to her ensemble blurs the boundaries between what women and men should and should not wear embodying and embracing ideas of gender fluidity. In addition, room 3 specifically looks at theatre and performance. The performative nature of fashion and clothing is evident here. We see ‘Soldiers in Skirts’ poster from 1945 and several 1920s photographs taken by Cecil Beaton where both men and women are dressed in women’s clothing and heavily made-up, often making it difficult to distinguish between male and female subjects.’

‘Queer British Art: 1861-1967 highlights the importance of fashion in queer art. Whether alleviating oppressions, dressing up, highlighting gender fluidity or questioning convention.’

‘We both really enjoyed the exhibition and it was ideal for giving us the wider context to life at Charleston.’

This is an exciting time for Charleston which has lent works by Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell to the Sussex Modernism exhibition at Two Temple Place, London, which runs until 23 April 2017, and to the Vanessa Bell: 1879-1961 solo exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, which is on until 4 June 2017. Later this summer, Clare Barlow will be speaking at Charleston’s A Gay Outing – further details will be announced on Charleston’s website.

Diana Wilkins and Vanessa Jones

[1] Tate Britain, ‘Queer British Art: 1861-1967’, Tate Britain (London), 2017