Highlights from the Gift

As we come to end of our six months together in the Charleston Attic we look back over pieces we have found in the Gift, but have not had the chance to write about.

CHA/P/2523 Recto. Duncan Grant, Tangiers Landscape, pastel and pencil on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

We have found another example of Grant’s sketches from El Farah, the house where he stayed in Tangiers, an unexpectedly extended vacation we discussed a few weeks ago. This sketch is annotated as “from El Farah” suggesting this is the view from Duncan Grant and Paul Roche’s ground floor bedroom-come-studio.

CHA/P/2552 Recto. Duncan Grant, drawing, Alfred Hitchcock, pen on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

Later in life Duncan Grant sketched from his television. Here we see a quick sketch of Alfred Hitchcock which Grant has signed, noting too that he completed the study from film. As Frances Spalding notes in her biography, in 1957 Grant saw television for the first time and wrote to Vanessa Bell “I really think it is the end of civilisation as we know it… but of course one can’t help glancing in its direction from time to time”.

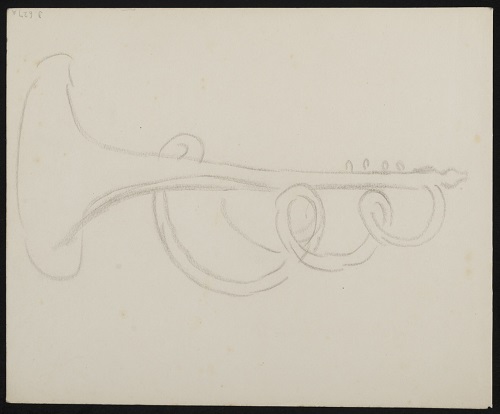

CHA/P/2472 Recto. Duncan Grant, study of a horn for poster “Musical Instruments for the Front”, pencil on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

This is a study for the poster that Duncan Grant designed in c.1918 which read “Wanted! Wanted Musical Instruments for the Front… If you have any musical instruments to give the soldiers at the front write at once”. The posters were printed by David Allen & Sons Ltd. Charleston has recently acquired one of the few remaining posters known to survive which alongside this preliminary study provides insights into his design practice.

CHA/P/2443 Vanessa Bell, Lithograph, London Children in the Country. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

One box that we have worked through during our time here contained various examples of woodcut prints and lithographs executed by both Bell and Grant. Read more about these prints and the significance of print making in both artists’ works in our previous blog here. This lithograph is by Vanessa Bell and is believed to illustrate the experience of evacuated children from the capital city in the countryside around the beginning of the Second World War. The print design dates from 1939.

CHA/P/2413 Recto. Vanessa Bell, painting, Berwick Church study, paint on canvas. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

This is a study of a lamb by Vanessa Bell which would go on to make part of her final mural design for The Nativity at Berwick Church executed in 1942. Berwick Church commissioned these murals by Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell in the early 1940s and they can still be seen today. You can walk from Charleston to Berwick Church; find the route on our walking maps available in Charleston’s shop.

CHA/P/2253 Recto. Duncan Grant, figure study, pen on newspaper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

This piece illustrates the inter-textuality of many of the works found in The Angelica Garnett Gift. Here Duncan Grant has penned a nude figure study on a page from The Nation, signing this sketch in a different pen at a later date, and adding the note “can’t make out/ don’t remember the sitter”.

As our season here comes to an end we welcome and wish good luck to the new Attic interns Emily Hill and Philippa Bougeard.

Zoe Wolstenholme and Rebecca Birrell