An Unexpected Frieze

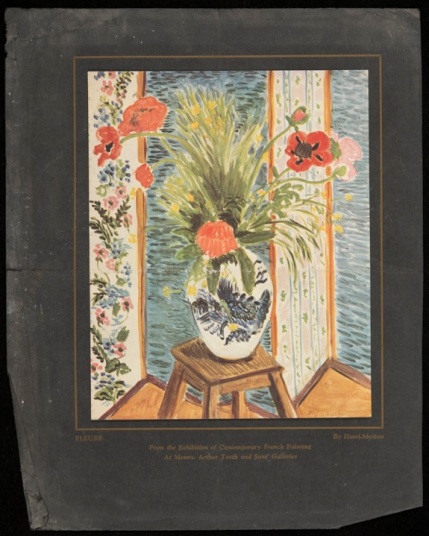

A beautiful frieze was re-discovered today! Under a magnifying lens we identified that the frieze was hand painted with a chalk based paint, applied onto plaster. Dating from around 1800, it is possible that a technique called fresco was used, which means the artist painted directly onto wet plaster. The frieze could have been used for a number of different decorative purposes: a mural, the edging of a frame or it could have been applied directly onto the wall. The frieze was not created by one of our Bloomsbury heroes however it was evidently a source of inspiration given that it has been carefully wrapped in brown paper.

CHA/P/3766, wallcovering frieze stuck onto squared paper wrapped in brown parcel paper with hand written annotation ‘Frise’, chalk based paint on plaster, c. 1800.

Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

Unfortunately only one of the two frieze examples survives. With only a small amount of debris left, the first almost non-existent frieze is decorated with shades of duck egg green. Much more intact, the other frieze is of an acanthus leaf which is painted in shades of brown with a delicate gold finish.

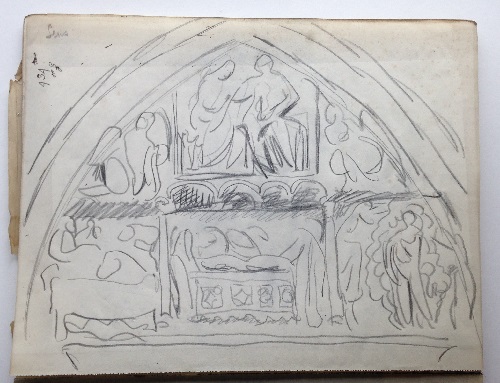

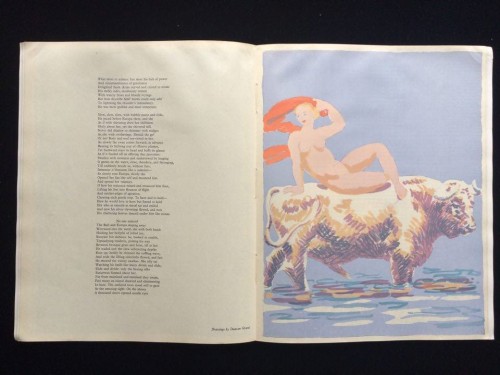

The frieze was in the middle of a sketchbook with ‘SENS’ written on the cover. It is likely that the sketchbook belonged to Duncan Grant as the book bears his name on the back page. As well as this, letters and postcards stored in the Tate’s Archive were sent from Sens, France by Grant to Vanessa Bell in December

1924.[1]

![Front [22 December 1924] by Duncan Grant 1885-1978](https://thecharlestonattic.files.wordpress.com/2017/05/sens1.jpg?w=500)

Postcard written by Duncan Grant to Vanessa Bell sent from Sens, 24 December 1924. Photograph © Tate Archives.

The paper ephemera contains Grant’s excitement after visiting Sens and Dijon Cathedrals, explaining how they make ‘a lovely drawing’.[2] Several pages in the sketchbook are of murals and biblical scenes that have probably been inspired by these Cathedrals.

CHA/P/3766, biblical scene with hand written annotation ‘Sens’, pencil on paper, c. 1924. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

On one of Grant’s many trips to France, this frieze has probably been removed from a building of some significance given the fine workmanship of the object. Could the frieze have come from one of these magnificent buildings Grant visited on his travels? There are many mysteries that surround this frieze, but what an excellent thing to re-discover in the middle of a sketchbook.

[1] In two letters to Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant speaks of his fondness of the cathedrals. Letters can be found at the Tate Archive: www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/tga-8010-5-1338/, www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/tga-8010-5-1337/

[2] Tate Archive, Postcard from Duncan Grant to Vanessa Bell, 24 December 1924, Online access: www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/tga-8010-5-1339

![0 T UMAX PowerLook III V1.5 [2]](https://thecharlestonattic.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/cha-p-174avb.jpg?w=500&h=395)