“New honours come upon him, like our strange garments”

When in Shakespeare’s Macbeth the tragic hero is named Thane of Cawdor in Act 1, his fellow general Banquo comments on how the position adorns him like a novel new outfit, not yet worn in: “New honours come upon him, / Like our strange garments cleave not to their mould, / But with the aid of use”. He posits that only with time will Macbeth wear his position better. Costume features as a trope within the play and here signifies both identity and pretence. Thus the costume of Macbeth was already layered with conceptual meaning before Duncan Grant embarked on his Modernist designs for Harley Granville-Barker’s production, planned for 1912. We have recently been working on Grant’s sketchbook for these designs, found in the Angelica Garnett Gift. Indeed, although they were never used in their original form, the sketches reveal Grant’s working design process and gives us a glimpse of the production that could have been.

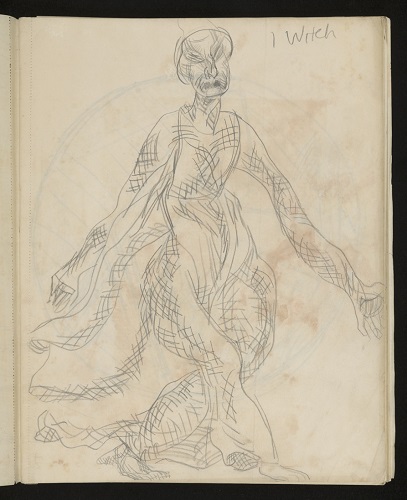

Duncan Grant’s designs (images below) include a costume for a witch, whose billowing crosshatched mantle gives the character a portentous presence, a simplistic dress for Lady Macbeth’s entrance, and Lords wearing robes made from Omega fabrics. There is also a page of notes that details Macbeth and Lady Macbeth’s costume changes over the course of the play. Lady Macbeth, for example, is first seen in a yellow/orange dress but her costume changes in mood so that by the Fifth Act she is wearing a grey crepe nightgown with dark blue cashmere wrapper spotted with dull Indian red. The dark Indian red spots that decorate her wrap mirror the blood that she struggles to wash away from her conscience in her line “out, damned spot”, revealing how Grant’s costume is both highly experimental whilst being sensitive to Shakespeare’s original script. These designs were a precursor to his costumes created for Copeau’s Twelth Night in 1914. In this production the costumes by Grant shone against a minimalist set where painted fabrics and Omega patterns such as Mechtilde were shown to their full advantage.

When this sketchbook was originally unearthed from the Angelica Garnett Gift, mould was found growing on the cover and some of the inside pages. Our paper conservator has worked on the sketchbook to remove the mould incrustations from the surfaces of the paper and covers, treating the object so as to destroy the mould spores. The cover was in such condition that the strawboard boards that supported the sketchbook covers were completely removed. The cover fabric itself has been preserved and is now catalogued into the collection with the separate sketchbook pages.

CHA/P/2584/6. Duncan Grant, Macbeth Sketchbook, costume design for Witch, pencil on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

CHA/P/2484/28. Duncan Grant, Macbeth Sketchbook, costume design for Lady Macbeth, pencil on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

CHA/ P/2484/50. Duncan Grant, Macbeth Sketchbook, costume design for a Lord, pencil on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

CHA/ P/2484/50. Macbeth Sketchbook, notes on costume designs for Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, pencil on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

Our Heritage Lottery Fund Public Programmes and Learning Intern is currently putting together a workshop that will engage volunteers from a local community costume resource to recreate some of the costumes from this sketchbook later this year.