Berwick Church murals – preliminary sketches by Duncan Grant

Prompted by a collection of drawings and sketches found inside a thin blue cardboard folder labelled ‘Berwick Church’ (CHA/P/603), this week’s blog article examines some of Duncan Grant’s preliminary studies for the painted wall murals created for Berwick Church in Sussex between 1941 and 1944.

On the 10 October 1943 a dedication service was held at St Michael and All Angels Church in Berwick Village in honour of the completion of a collection of new wall murals designed and painted by local Bloomsbury artists’, Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and her son Quentin.

Although they had been commissioned in 1940 by Brighton-based, Bishop Bell, the designs were not fully approved by Berwick’s Parish Church Council until a year later. It was recommended that the murals be painted on plasterboard panels which were constructed in a barn at Charleston.[1] The first set of murals entitled The Annunciation and The Nativity by Vanessa Bell, Christ in Glory by Duncan Grant and The Wise and Foolish Virgins by Quentin Bell were largely finished by January 1943 and raised into position by spring that year.[2]

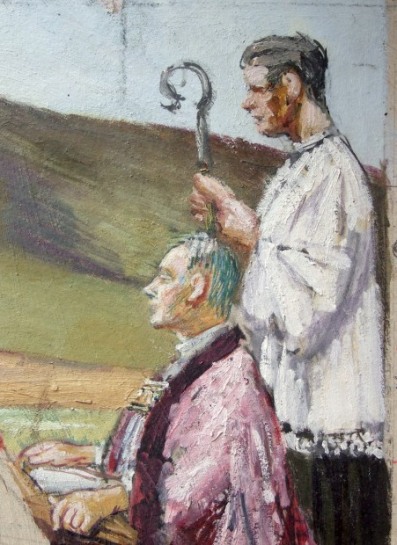

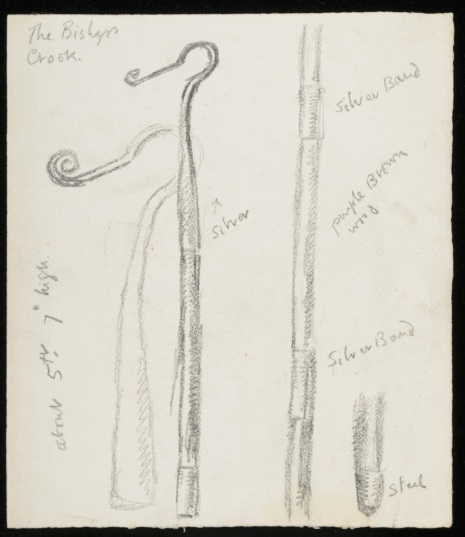

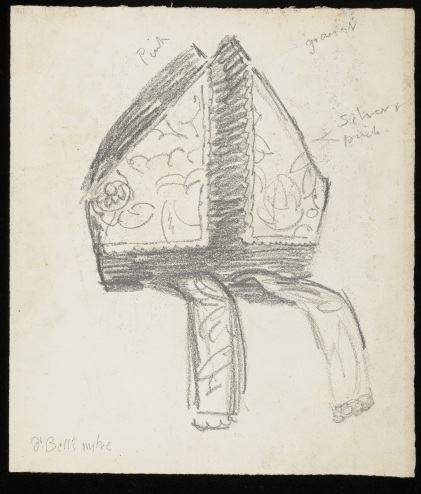

The first few sketches in the folder are connected with Bishop Bell himself, besides a full portrait study of him kneeling, there is a detailed study of his mitre and his crook. These were preliminary sketches for the figure of Bishop Bell as represented in the group of church officials to the right hand side of the arch in Christ in Glory.

CHA/P/603/9, Duncan Grant, Dr. Bell kneeling, c. 1943. © The Estate of Duncan Grant. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

Berwick Church murals, Duncan Grant, detail of Bishop Bell kneeling, c. 1942. © of the Estate of Vanessa Bell 1961 and the Estate of Duncan Grant 1978, courtesy of Henrietta Garnett. Photograph: berwickchurch.org.uk/bloomsbury.

CHA/P/603/4, Duncan Grant, The Bishop’s Crook. © The Estate of Duncan Grant. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

CHA/P/603/3, Dr. Bell’s Mitre, c. 1943, © The Estate of Duncan Grant. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

For Grant, Bishop Bell was

‘a most obliging sitter, going down on his knees so that Duncan could draw him in the position he wanted and lending him his elaborate crosier, robes and mitre so that work could continue in his absence’.[3]

However, work on the church decorations did not end with the dedication service. In April 1944 a new Faculty was granted for decorations to the chancel screen and pulpit, a crucifixion on the west wall and an altar picture.

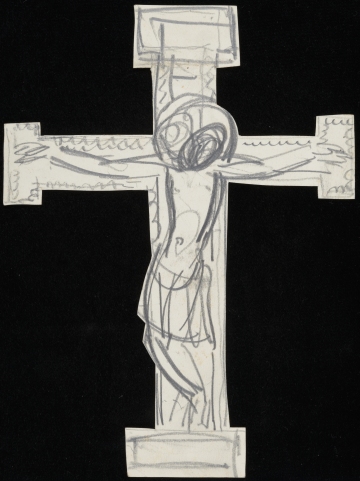

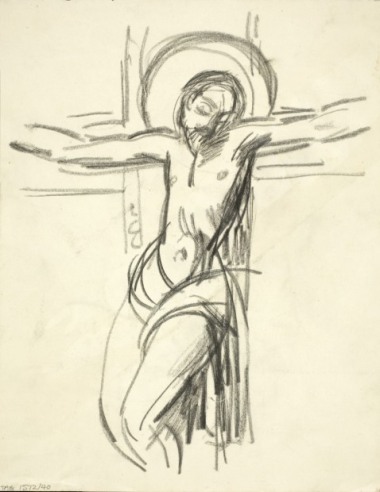

The last two sketches in the blue folder (CHA/P/603/14 and CHA/P/603/11) appear to be preliminary designs for The Crucifixion or The Victory of Calvary, a mural of Christ on the cross completed by Duncan Grant in 1944.

Duncan Grant, The Crucifixion or The Victory of Calvary, Berwick Church mural, 1944, © of the Estate of Vanessa Bell 1961 and the Estate of Duncan Grant 1978, courtesy of Henrietta Garnett. Photograph: berwickchurch.org.uk/bloomsbury.

CHA/P/603/13, Duncan Grant, preliminary sketch for The Crucifixion, c.1943, pencil on paper, Berwick Church murals. © The Estate of Duncan Grant. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

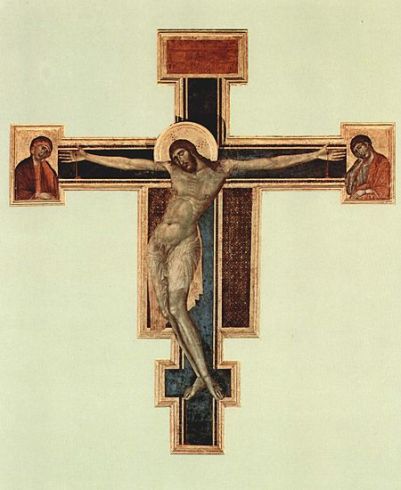

Likely to be experimenting with ideas for the composition of Christ, Duncan Grant was clearly influenced by his admiration of early Italian Renaissance art in this pencil sketch. He had visited Florence some forty years earlier in 1904 with his mother Ethel and spent every day at the Uffizi copying works by artists such as Piero della Francesca and Masaccio.[4] It is also likely that he visited Basilica di Santa Croce, the main Franciscan church in Florence where he would have seen Crucifix, 1287–1288 a work by Cimabue which probably provided inspiration for his later pencil study.

Cimabue, Crucifix, 1287–1288. Distemper on wood panel, 448 cm × 390 cm. Basilica di Santa Croce. Photograph: The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei.

Grant particularly favoured the work of Michelangelo, in the autumn of 1910 he was copying Entombment c. 1500-01 at the National Gallery in London.[5] In his sketch for The Crucifixion mural Christ’s head is depicted in a bowed position, slightly crooked to one side echoing the pose of Christ’s head in Michelangelo’s painting.

Michelangelo, Entombment, c. 1500-01, tempura on panel, National Gallery, Photograph: National Gallery.

Duncan Grant, preliminary sketch for The Crucifixion or The Victory of Calvary, Berwick Church mural, 1944, © of the Estate of Vanessa Bell 1961 and the Estate of Duncan Grant 1978, courtesy of Henrietta Garnett. Photograph: berwickchurch.org.uk/bloomsbury.

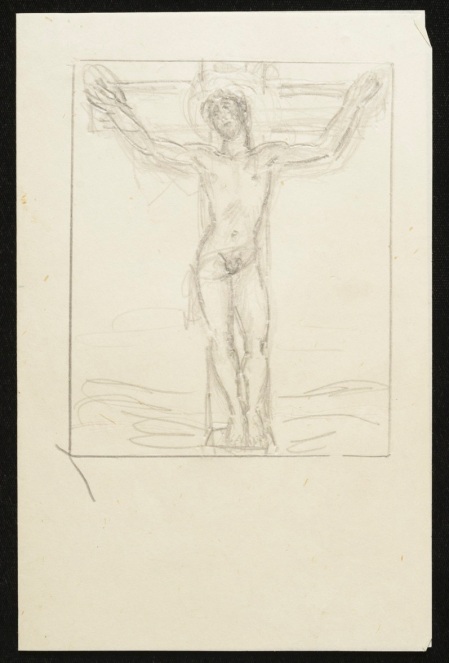

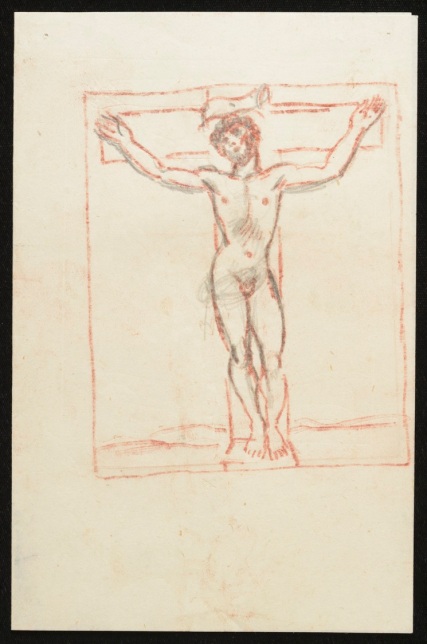

In the preliminary sketch by Grant for The Crucifixion shown on the Berwick Church website, Christ is drawn in more detail; the head is still in the same position as in CHA/603/13 but the loin cloth is draped differently. In the coloured version of the drawing, the head is straighter and the cloth is tied and more full rather than draped. However, Christ’s torso in Grant’s coloured study CHA/P/603/11 is similar in shape and composition to that in Cimabue’s work.

CHA/P/603/11, Duncan Grant, preliminary drawing for The Crucifixion, Berwick Church mural, c. 1943, gouache on paper. © The Estate of Duncan Grant. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

Edward Le Bas, a close friend of Duncan Grant modelled for the figure of Christ in The Crucifixion mural.[6] When compared with the sketches detailed above, two other studies CHA/P/2543 and CHA/P/2544 in the Angelica Garnett gift catalogue certainly seem to indicate that Grant was sketching from a life model, especially considering the detail depicted in muscle definition and proportion. Moreover, the head position, raised and looking upward to the right side is also nearer to that of the finished mural.

CHA/P/2543 (above) and (below) CHA/P/ 2544, Duncan Grant, preliminary study for The Crucifixion, Berwick Church mural, c. 1943, pencil on paper, © The Estate of Duncan Grant. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

It was in 1943, at the time that Grant was working on the church murals that Edward Le Bas first visited Charleston. He recalled his visit in a letter to Grant dated 2 July 1943:

‘I did enjoy the weekend, you’ve no idea how much: to see again how life can really be lived [….] The church paintings grow in my mind in calmness and power.’[7]

References:

[1] Frances Spalding, Duncan Grant: A biography, Pimlico, London (1998), p. 382.

[2] http://www.berwickchurch.org.uk/bloomsbury%20at%20berwick%20home.html

[3] Frances Spalding, Duncan Grant: A biography, p.384.

[4] Ibid., p.33.

[5] Ibid., p.97.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., p.397.