Grant, Hughes and Hogg: A Vision of History

Every once in a while we find an item in the attic that is as perplexing as it is interesting and requires some serious investigation to decode its meaning. Such an item came to our attention this week; a charming sketch of a man in historical costume with two names in the hand of Duncan Grant inscribed on the back; those of Talbot Hughes and John Hogg.

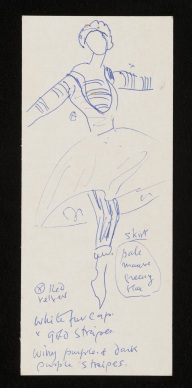

(top) CHA/P/1783-R, Duncan Grant, drawing, study from Talbot Hughes’ ‘‘Dress design: an account of costumes for artists and dressmakers, illustrated by the author from old examples, pencil on paper, 33.2 cm x 26 cm. Photograph © The Charleston Trust (bottom) CHA/P/1783-V, Duncan Grant, drawing, study from Talbot Hughes’ ‘Dress design: an account of costumes for artists and dressmakers, illustrated by the author from old examples, pencil on paper, 33.2 cm x 26 cm. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

The name Talbot Hughes is familiar, practising as a genre artist exhibiting at the Royal Academy and the Society of British Artists he also amassed a large collection of English historical costumes and accessories, dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. An admirer of the French classicist painter Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, Hughes was meticulous in his attention to detail and his extensive costume collection allowed him to style his models for his artworks accurately. The 752 piece collection of garments and accessories were sold to Harrods in 1913 for the sum of £2,500 and were displayed at the store for three weeks before they were sent to the Victoria and Albert Museum, where they went on display on Christmas eve 1913.

In comparison to the wealth of information about the life, art and collections of Talbot Hughes, details about John Hogg proved to be more elusive and the connection between the two hard to fathom. It was when research revealed that Hogg had been a publisher working in London in the early twentieth century, publishing titles such as ‘Silverwork and Jewellery: a textbook for students and workers in metal’ that things began to fall into place.

In the year that Hughes sold his collection to Harrods he also collaborated with Hogg in the production of a book titled ‘Dress design: an account of costumes for artists and dressmakers, illustrated by the author from old examples.’ The contents of the book demonstrate the wealth of Hughes’ knowledge on the subject and the varied nature of his collection with chapters ranging from ‘prehistoric dress’ to ‘the character of decoration and trimmings of the eighteenth century.’ Adorning the pages of the 1913 edition are illustrations of costumes throughout the ages by Hughes, demonstrating the attention to detail he is known for in his paintings. Grant’s drawing that we found nestled in the boxes from the Angelica Garnett Gift appears to be a study from this book, his handwritten notes on the back providing helpful clues to the images origin.

(top) Fig. 79, Talbot Hughes, Dress design: an account of costumes for artists and dressmakers, illustrated by the author from old examples, Published by John Hogg, London 1913. Photograph © Gutenberg.org (middle) Fig. 91.7, Talbot Hughes, Dress design: an account of costumes for artists and dressmakers, illustrated by the author from old examples, Published by John Hogg, London 1913. Photograph © Gutenberg.org Fig. 81, Talbot Hughes, Dress design: an account of costumes for artists and dressmakers, illustrated by the author from old examples, Published by John Hogg, London 1913. Photograph © Gutenberg.org

Previous blog posts such as ‘Ballet and the Bloomsbury Group’ have explored Duncan Grant’s artistic relationship with costume design and the theatre. Grant’s practice of studying artworks for his own artistic development and for inspiration has also been explored in relation to the Angelica Garnett Gift with a blog post about the studies of Raphael. Why Grant chose this particular costume to sketch we can only speculate, it may be that there are many other costume studies yet to be found in the Gift. We know that Grant was commissioned in 1914 to produce costumes for Jacques Copeau’s adaptation of Twelfth Night by Theodore Lascaris, a creative collaboration between the two men that was to continue until the outbreak of war in 1918. Designing the costumes for the production Grant desired to sustain the mood of comedy and as a result ignored details such as hats and swords, neglecting historical reality in favour of shape and fluidity, something Hughes no doubt would look upon negatively. Earlier in our exploration of the Gift we uncovered possible sketched designs for a production of Macbeth by Granville Barker in 1912, a project which was later abandoned in 1913. Could the study of historical costume found this week in the attic be connected to either of these Shakespeare productions or does it represent Grant’s artistic diversity and self-imposed life long education as an artist? Whatever the sketch’s original purpose, today it represents a fascinating insight into Grant’s artistic practice, as well as being a beautiful and interesting drawing.

CHA/PH/2. Photograph. Nijinsky in the Siamese Dance from ‘Les Orientales,’ 1911, by Druet. 26.5 x 43.6 cm. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

CHA/PH/2. Photograph. Nijinsky in the Siamese Dance from ‘Les Orientales,’ 1911, by Druet. 26.5 x 43.6 cm. Photograph © The Charleston Trust