Judging a Book by its Cover

Recently in the Charleston Attic, in amongst a box full of bold charcoal studies and painted designs, we found a book cover without a book. The hardback has been separated from the papers it once bound together. Either torn off to create an object of its own, or worn away from its pages by years of use, we have only the cover by which to guess about the book itself.

CHA/P/2311 Recto. Painting, abstract motifs, paint on book cover. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

This intriguing piece has inspired speculation in the Attic. Perhaps it was painted to represent the book that it held. Green and blue leaves hang across from the right edge as if growing from the now missing pages that the cover would have opened onto. It is as though the story is almost spilling from the pages onto the cover. Book design and illustration were, indeed, a part of the Bloomsbury oeuvre. The Omega workshops published books bound with designs by Dora Carrington and Roger Fry; Virginia and Leonard Woolf established the Hogarth Press in 1917 where they printed works including T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and David Garnett’s Lady into Fox; and Virginia Woolf published many of her own works on the Hogarth Press, with covers designed exclusively by her sister Vanessa Bell from 1919. Frances Spalding writes about this sisterly enterprise commenting that

“this collaborative work encouraged consideration of the relationship between literature and art. Formerly Virginia had on occasion been slightly repelled by the Bloomsbury painters’ insistence on purely visual qualities. Now suddenly her interest in painting grew stronger; she visited the National Gallery and tried to describe to Vanessa her response in front of certain paintings… In turn Vanessa began to take a more critical interest in books”.

The sisters’ works came together in book design, Vanessa Bell interpreting Virginia Woolf’s words in image, distilling moments from literature in art. Bell was particularly interested by Woolf’s short fiction, writing to her in July 1917 “why don’t you write more short things […] there is a kind of completeness about a thing like this that is very satisfactory and that you can hardly get in a novel”.

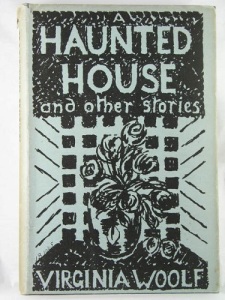

CHA/BKS/29. Book, “A Haunted House”, Virginia Woolf, with original dust jacket by Vanessa Bell, The Hogarth Press, London, 1947. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

CHA/BKS/30. Book, “The Death of a Moth”, Virginia Woolf, with original dust jacket by Vanessa Bell, The Hogarth Press, London, 1947. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

The cover design that we have found in the Attic would have made a fitting dust jacket for Woolf’s impressionistic short stories Green and Blue. It has been noted by Benjamin Harvey in his essay on Virginia Woolf, Art Galleries, and Museums that the presentation of these stories, side by side on opposite pages, creates an “imagistic diptych”. The stories are almost like two paintings hanging next to each other. Thus Harvey suggests that Woolf’s style is almost curatorial. Indeed the painterly qualities of Woolf’s prose compares to the fluid brushstrokes on the book cover here in the Attic. Moreover, the imagery on the recto reflects the short story Green which opens with the lines:

“The pointed fingers of glass hang downwards. The light slides down the glass, and drops a pool of green. All day long the ten fingers of the lustre drop green upon the marble. The feathers of parakeets—their harsh cries—sharp blades of palm trees—green, too; green needles glittering in the sun. But the hard glass drips on to the marble; the pools hover above the desert sand; the camels lurch through them; the pools settle on the marble; rushes edge them; weeds clog them; here and there a white blossom; the frog flops over; at night the stars are set there unbroken”

The book cover seems to mirror this description. The green leaves on the right transform from glass to feather and back to palm tree leaves only to abstract into the green dots on the left, just as Woolf’s glass “drips on to the marble”.

CHA/P/2311 Verso. Painting, acrobatic figures, paint on book cover. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

The inside cover depicts a wholly different design of three acrobatic figures underneath a scallop-edged and star-studded hole. This hole is made more obvious here, camouflaged somewhat by the abstract foliage on the front. This led us to ask whether the hole could have provided the means for the young Julian and Quentin Bell to spy on the adults under the pretence of study at Charleston during their lessons in the orchard. A visitor to the Attic also proposed that this could be a gunshot hole, which could very well have been inflicted upon an unsuspecting book in the garden during Julian and Quentin Bell’s childhood experiments with their air gun. However, the cut out hole follows a delicate pencil outline, drawn on the verso side, suggesting this was part of a larger and premeditated design.

Indeed, the hole and the verso design suggest an entirely different use for this book cover. Perhaps the cover was not decorated to represent the book that it held but was reclaimed and refashioned into a work of its own. If so, it is similar in style to Quentin Bell’s painted ceramic reliefs and “goggle-boxes” in which figurines adorn plates and can be spied upon through peepholes populating rooms from different eras. One particular ceramic design, Mademoiselle Zedel, the Human Cannonball, depicts a female performer bursting through a screen held by two male acrobats in matching leotards. Our book cover could perhaps be a precursor to this piece in which the three figures are preparing for Mademoiselle Zedel’s launch that culminates in Bell’s ceramic work. Perhaps she is preparing to fly through the hole in the book cover above their heads.

It is quite possible that Quentin Bell’s works and designs could be found amongst the sketches and preparatory works of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant in the Attic as Quentin Bell spent much of his childhood at Charleston and had a ceramic studio here from 1937 when his first kiln was installed. Simon Watney writes of how, much later, in the 1960s

“on most weekday mornings Quentin would let himself into the house and pad straight through to his pottery, which opens off the little walled garden that is reached from Duncan’s studio. […] Quentin cut a burly figure in his big blue overalls, often smeared with slip, or splashed with colour if he was decorating. The small talk was often hilarious. Here Duncan and Quentin met as artists.”

We can imagine the book cover left to one side in Quentin’s ceramic studio before he set out into the house for lunch. Or maybe the work he was doing now had been inspired from studies such as this book cover painted earlier in life.

Whatever its purpose and whoever its creator, it fits in very well at Charleston. Its painted cover is like the patterned walls and furniture, inspiring us that any object can provide a canvas. We imagine it blending in very nicely with paintings and other books – perhaps some wearing Quentin Bell’s c.1935 dust jackets – on a table in the studio downstairs.

CHA/P/440. Dust jacket, Quentin Bell, “Heredia”, circa 1935, gouache. Photograph © The Charleston Trust