Lyric Charm and Quiet Wit

The Angelica Garnett Gift never fails to surprise with its traces of Charlestonian foreign travel. Amongst a scattered geography of postcards, sketchbooks and letter paper, we have followed Bell and Grant from the winding backstreets of St. Tropez to sites of classical antiquity in Greece. This week the tokens of travel are a pair of vibrant landscapes from Duncan Grant’s 1975 visit to Tangier.

CHA/P/2594. Duncan Grant, Recto. Tangier Landscape. Oil pastel on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

At 91 Grant remained a keen traveller, so on 17th October 1975 he took a late flight from Heathrow to Tangier with companion Paul Roche. Grant planned on passing a tranquil few weeks painting at El Farah, the home of friend Rex Nan Kivell, a former hotel three miles outside of Tangier with which Grant was by now familiar, having stayed twice before in the late sixties. Due to Grant’s reduced mobility, the pair slept downstairs in a room with magnificent views of the town, surrounding countryside, and distant glimpses of the sea. Yet Grant delighted most in his immediate environs, as Paul Roche recalls:

‘He was enchanted by the cacti, the hibiscus, the bananas and the heavily scented long ivory funnels of datura.’

However, disaster soon struck: as a result of damp and cold evenings in El Farah, Grant soon contracted pneumonia. A brief and pleasant holiday became a lengthy mission to stabilise Grant’s health, with he and Roche finally leaving on his full recovery seven months later.

Once the worst of Grant’s illness had passed, Roche recalls idyllic days of drawing and dining, paying visits to the local artistic elite (such as Paul Bowles and Marguerite McBey) alongside hours devoted to their creative projects. Remembering Grant’s aesthetic during this period, Roche remarks:

‘Unable to command the solidarity of a portrait or a still-life anymore, Duncan had let loose his lyric charm and quiet wit.’

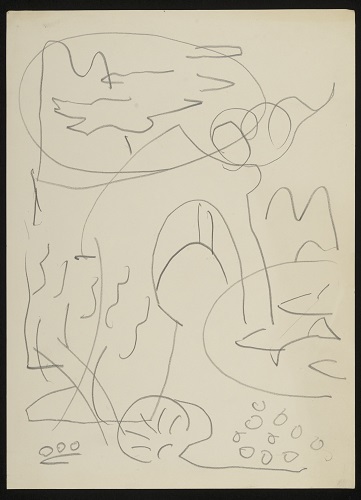

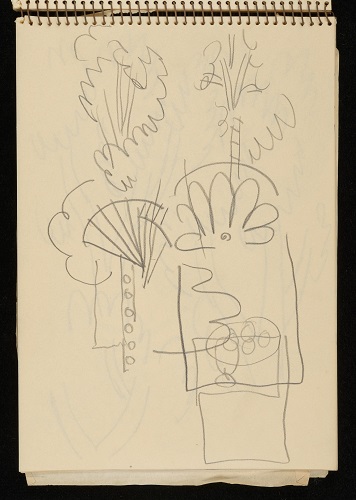

These Tangier landscapes are certainly instances of such ‘lyric charm’, rendering local flora and fauna in astonishingly bright blues and purples, executed with an abstraction closer to the experiments of his youth. Like many of the pieces from his time in Tangier, one can imagine these works completed at the large circular table of Grant’s make-shift studio, with Roche reading on an adjacent divan, or cycling into town to purchase their lunch.

CHA/P/2595. Duncan Grant, Recto. Tangier Landscape. Oil pastel on paper. Photograph © The Charleston Trust.

Their preservation in the gift is itself a stroke of luck. Thanks to months of roaring hot fires (in a desperate attempt to buoy Grant’s strength) El Farah’s sumptuous interiors were almost entirely ruined by smoke, soot and ash. This is not to mention Grant’s rather puckish approach to the villa’s soft furnishing. While a tablecloth cut into fanciful patterns could be easily concealed, Grant’s other transgressions were more obvious: the grey velvet upholstery of an armchair was refashioned into a dashing Post-Impressionist design, if somewhat frustratingly for Kivell with the use of a black permanent marker. As a result, Roche was eager to offer Grant’s works as recompense; yet Kivell was sympathetic to the pair’s plight, gratefully receiving only a small watercolour of an orange.

The remaining pieces we can only assume returned home with Grant and Roche, after a long internment in the ad-hoc home they created out in Morocco.