The Bell of the Ball

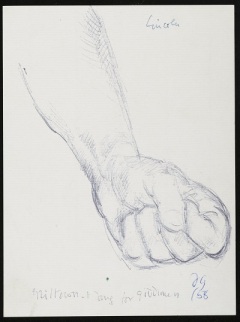

It is very easy to get lost in imagining the world, people and stories behind the pieces in the Angelica Garnett Gift and this preparatory sketch by Duncan Grant for a mural designed by both Grant and Vanessa Bell is no exception.

CHA/P/1117, Duncan Grant, Cinderella, coloured pencil on paper, date unknown, 29.5 cm x 23 cm. Photograph © The Charleston Trust

The mural was commissioned by the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts and the British Institute of Adult Education in 1943 for the dining hall of Devonshire Hill School in Tottenham. The design by Grant and Bell depicted the fairytale Cinderella, and was completed during World War II. Sadly, the mural no longer exists, having been dismantled and destroyed during renovation works at the school. Perhaps even more regrettable is that few people are aware that it existed at all. Like many other decorative works by Grant and Bell all that now remains are a few photographs, newspaper cuttings and preparatory drawings, such as one discovered during the last week in the Charleston Attic.

Maynard Keynes, or Lord Keynes as he was then known, described the murals at their unveiling as ‘rather humorous, deliberately light, pleasing and anecdotal.’ This expressive sketch perhaps shows Cinderella being presented at the ball where she was to meet her Prince Charming. The theme of Cinderella lends itself well to the work of Grant, given his interest in theatre and costume design.

The completed mural was unveiled in February 1945, although Grant was not present due to illness. The evening took a theatrical theme as the mural was revealed panel by panel with assistance of former pupils of the school against the backdrop of whimsical commentary by Lord Keynes. Newspaper cuttings from the time describe how the audience found themselves;

‘moved by this charming part of the ceremony, demonstrating as it did what a magnificent contribution had been made to beautifying the dining room of the school.’

Top: Photograph of Cinderella Mural, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, The Devonshire Hill School Tottenham, date unknown. Photograph © Bruce Castle Museum Bottom: Photograph of Cinderella Mural, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, The Devonshire Hill School Tottenham, date unknown. Photograph © Bruce Castle Museum

Top: Photograph of Cinderella Mural, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, The Devonshire Hill School Tottenham, date unknown. Photograph © Bruce Castle Museum Bottom: Photograph of Cinderella Mural, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, The Devonshire Hill School Tottenham, date unknown. Photograph © Bruce Castle Museum

Representatives of both the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the British Institute of Adult Education were in attendance and Mr Peverett on behalf of the British Institute expressed the hope that;

‘such mural paintings, as now adorned the school would lead to a new age in education in which appreciation of art would spread through the education system.’

The Committee from the British Institute were also conscious that the general public should have access to the murals and as a result for one week in August the public were invited to the school each evening from Monday to Saturday, 7-9pm, as part of the Holidays at Home Programme.

There were several initiatives during the Second World War for the creation of arts in Britain. As early as 1940 government officials had identified a link between public moral and available programmes of art. The Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts aimed to foster the arts through state funded programmes and looked towards a Britain in peacetime where art would become an integral part of everyday life. Kenneth Clark, a long term supporter of Grant, Bell and the Bloomsbury group, was a government official during the war and stressed that what was called for was ‘something to occupy peoples minds,’ and he was determined that the government ‘take some active part in stimulating activities of this sort.’ Indeed it was a result of this initiative and the subsequent interest in the arts as a whole that led to the formation of the Arts Council in 1946.

Cinderella was the second joint commission that Grant and Bell undertook during the Second World War; the first and most documented being that for Berwick Church, these completed murals being still in existence today. In 1939 both artists had joined the Society for Mural Painters and had been represented at the Society’s first exhibition at Tate with photographs of their decorative schemes. Although such projects were perhaps sparse during the war years, Bell and Grant continued to work and produce art between commissions. Grant travelled to Plymouth as a war artist to depict the men defending Britain as gunners whilst the Tate negotiated the acquisition of his large painting Angelica Playing the Piano and Bell arranged an exhibition of new works with the Leicester Galleries amongst other projects.

A newspaper article reporting on the unveiling of the Cinderella murals remarked on the hope that;

‘this delightful work of art will remain for long as a treasured possession of the borough and will be seen as the days go on by many of its citizens, both young and old.’

Cinderella puts on the shoe, Vanessa Bell, date unknown. Photograph © Bruce Castle Museum

We now know today that this was not to be the case. As with so many decorative schemes by Grant and Bell the mural has been a victim to changing taste and spatial needs, the dining room where it once was such a prominent and charming feature now serving the function of an assembly hall. Despite the relative obscurity of the scheme sketches for the mural remain and one such piece ‘Cinderella puts on the shoe,’ by Bell is currently in the possession of Bonham’s auction house.

Even though it is important to remember this mural as an example of the artistic talents and storytelling abilities of both Grant and Bell, it is also vital that we consider it as an example of the government’s desire to bring beauty and hope into the often desolate and desperate lives of communities during the Second World War.